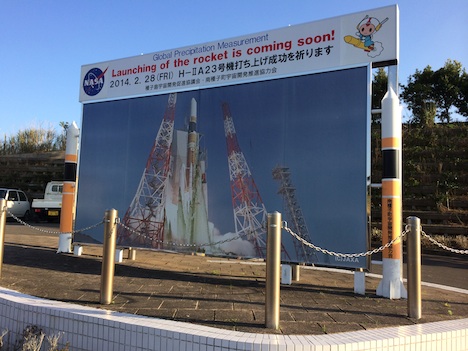

Welcome to Minamitane, Japan. A billboard announcing GPM’s launch on Feb. 28 th (27th in the U.S.) at the nearby Tanegashima Space Center greets visitors as they come into town. Credit: NASA / Ellen Gray

At the town line into Minamitane on Tanegashima Island, Japan, a giant billboard announces, “Global Precipitation Measurement / Launching of the rocket is coming soon!”

Six days to be exact.

I grinned when I saw it. Global Precipitation Measurement, or GPM, is why I’m in town. The launch window begins at 1:07 p.m. Feb. 27 (U.S. EST) / 3:07 a.m. Feb 28 (Japan ST).

I’m Ellen Gray, the science writer for the mission. Over the coming week before launch, video producer Michael Starobin and I will be reporting from the launch site as the GPM team in Japan works with NASA’s mission partners, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, on the final preparations before liftoff.

“Global Precipitation Measurement” is a mouthful, but an accurate one. The mission is going to measure all types of precipitation — rain, snow, hail, and that slushy winter mix — across nearly the whole globe, every three hours. When people hear me say that, the question I get is how is one satellite going to do all that? The short answer is that one satellite can’t do it by itself.

The overarching GPM mission consists of more than one satellite. The big picture of global rainfall comes from the combined observations of many rain and weather satellites operated by different countries or agencies. Each satellite has a similar instrument that measures precipitation, and all that data combined is what gives you the global picture.

The GPM Core Observatory — the satellite launching next Thursday — is going to pull all the measurements from the different satellites together into a single data set. Observations from its radiometer will act as the standard to unify all the other satellite measurements. The Core Observatory’s second instrument is a radar, and together with the radiometer, scientists won’t just be seeing where it’s raining, they’ll be able to study how raindrops and ice particles behave within clouds, and ultimately Earth’s water cycle, in detail they couldn’t before. And it’s the first precipitation mission designed to send back measurements of light rain and snow, two of the trickiest types of precipitation to measure from space.

[youtube RlFFpzfXwYc]

Stay tuned for a busy week from Tanegashima. You can find the latest mission updates, stories and videos at http://www.nasa.gov/gpm. For photos, Bill Ingalls (@nasahqphoto) will be posting daily to the GPM Mission Set at NASA HQ Flickr. You can also follow the mission on twitter @NASA_Rain and on Facebook. For more in depth information on the GPM mission, Earth Matters put together a nice primer of videos and links. And, of course, we’ll be blogging right here under GPM in Japan, the Road to Launch.

Live coverage of launch will begin at 12:00 p.m. Feb 27 (EST) on NASA TV and online at: http://www.nasa.gov/ntv

Will this technology be used to counter-act certain storms that may be dangerous to a certain area ?